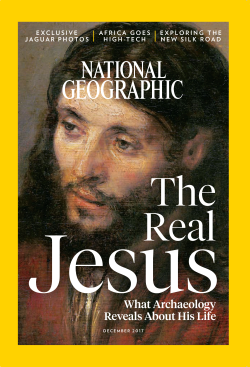

Looking for the Real Jesus… with Science?

The National Geographic recently put out a piece about searching for the real Jesus. Check out Bruce Seraphim Foltz’s take down.

The fallacy of “begging the question” refers to assuming that you are right. Assuming you are correct is the most common logical fallacy. Everyone does it at some point. If Kant, Aquinas, Aristotle, and Hegel do it, then what hope is there for us mortals?

We all beg the question. We all assume we are right. What do we do about it?

For me, when I find myself committing this fallacy, I try to catch myself. Better yet, I try to humbly acknowledge it when an interlocuter catches me out. Then I try to provide real arguments.

That seems to me the best way: Acknowledging and providing real arguments. That’s what I want others to do, so why not start with myself?

Regardless, it is easy to catch people begging the question.

Authors, writers, and conversational partners very often assume without argument that they know something important.

Often the argument goes like this: assume some big truth with certainty, then proceed to point out all the little truths that would follow if the first point were right.

Problem is, of course, that you haven’t shown the big truth to be actually true.

My friend Jesse once described this process of question begging as “axiomatic reasoning with B.S. axioms.”

The same problem occurs in this article searching for the real Jesus.

It’s good to search for the real Jesus. It’s good to search for the real anything.

Searching for the real X means that you are thinking scientifically, philosophically, and critically. Don’t take appearances as final. Look under the surface. See through deceptive appearances.

We agree on the what, but much depends on the how.

How does one search for the real sun? Not by psychology but astronomy.

How does one search for the real story of the Vietnam war? Not by astronomy but by history and political science.

How does one search for the real Jesus? By archeology and atheistic axioms? Or by history, philosophy, prayer, fasting, and conversation with those who follow Jesus as a God.

The Nat Geo article merely assumes that one can and should find the “real Jesus” through science. The big assumption is that material sciences are the only, or the best, paths to discovering reality. Call this assumption “scientism.”

Of course it follows from scientism that one should investigate the ‘real Jesus’ in the same way one investigates the real anything: real history, real physics, real astronomy, real psychology will all turn out to be material and hence best studied through material sciences (as far as possible).

Scientism, as an axiom, is perfectly respectable. Many people approach the world as if the only way to know anything is to use all the sciences, and only the sciences. They get by.

The question, for those of us who do not accept the axiom already, is whether we should adopt the axiom. Is there any evidence that scientism is true? Those of us who accept that abstract philosophical reasoning, revelation, and memory are reliable sources of truths also accept the accurate deliverances of all the sciences. What reason is there for believing that only the sciences (howsoever we define them) are reliable means to truth?

To answer this, step back and look at a deeper problem.

How could you possibly prove that scientism is a true? How could you possibly transform it from a mere assumption or axiom to an established truth?

By scientism’s own lights, you must use one or more sciences to prove scientism to be true. Otherwise, it is simply an assumption.

Certainly, science is so reliable we might want to jump to the conclusion that only science is reliable. But it’s a risk. It’d be better to prove the conclusion, if possible.

But it seems obvious to me that in order to prove that there are no other available means of discovering reality, you’d have to reach outside the empirical methods of the material sciences.

For example, you’d have to make an epistemological argument.

Epistemological arguments can and do certainly incorporate the latest information from the sciences (from psychology or the neurosciences, for instance). But epistemologists fundamentally use the abstract methods of philosophy. They use arguments, not “studies.” Their raw material is abstract, not concrete. They use thought experiments, not experiments. They do not study knowledge direcetly; they study the writings of other epistemologists.

I grant that I’m simplifying. But isn’t this argument somewhat simple?

If all this is right, then one of two things turns out to be true.

- First, if scientism could be proven true through abstract methods of philosophical reasoning, then scientism is false.

- Second, if it’s false that you can only know through the empirical methods of material sciences, then scientism is also false.

- Either way, scientism is false.

The dilemma the scientistic thinker must confront is that his belief in scientism itself cannot be scientifically supported.

One response would be that epistemology is or can be brought under the domain of ‘science’ broadly construed.

I would welcome this response. I think ‘natural philosophy’ (what we call ‘science’) is a science, broadly construed; just as logic and metaphysics are sciences in that broad sense.

The belief that there are only empirical methods of proof cannot be proven empirically.

And the response that science broadly construed uses more-than-empirical methods of proof (with which I agree) admits the full suite of valid methods into the search for the real Jesus: psychological, philosophical, etc.

I would put the point even more strongly: scientism (narrowly construed) is necessarily false. For those who understand the terms, it is impossible to believe that the empirical methods of material sciences are the only available means of discovering reality.

For this reason, it is more logical to do what philosophers and scientists like Plato and Galileo have always done, which is to discover reality through a combination of methods that, together, aim to canvass all domains of reality which are available to our scrutiny. We use a combination of logical, practical, sensory, empirical, scientific, and experiential methods and we investigate in a variety of domains.

When it comes to investigating the claims of Jesus Christ, we should not and will not arbitrarily limit ourselves to one method. We will look for “the real Jesus” in a variety of ways – including prayer and reading the Gospels.

All that said, I cannot force you to confront your own question-begging assumptions any more that you can force me confront mine. But we can invite each other to reflect and so humble ourselves.